Mostbet onlayn bukmekerlik kontorasi bilan tiking va 4 000 000 UZS pul yutib oling

Xalqaro darajadagi bukmekerlik kontorasi O’zbekiston va MDHning boshqa mamlakatlarida faoliyat yuritmoqda. Mostbet BK mosbet.com, hamda oyna va redirektlar manzillari orqali mavjud. Maqolada mostbetuz -ni kompyuterga qanday yuklab olish va Mostbet Casino-da o’ynash haqida aytib beriladi. Siz mosbet uz da ro’yxatdan o’tishning o’ziga xos xususiyatlari, bonuslar va doimiy o’yinchilar uchun sodiqlik dasturlari haqida bilib olasiz Android va iOS uchun Moostbet Uzbekistan.

Mostbet Bonuslari 125% + 250FS

| 🏗 Tashkil etilgan yili | 2009 |

| 📜 Litsenziya | Kyuracao |

| 💰 Bonus | 4 000 000 UZS |

| 🔥 Minimal tikish | 1 500 UZS |

| 💻 Mobil versiyasi | Ha |

| 📱 Mobil ilova | Android, iOS |

| 🇺🇿 O’zbek tili | Ha |

| 💵 Hisob valyutasi | UZS, USD, EUR, RUB, UAH, KZT |

| 🗳 Tote | Ha |

sayt mostbet.com Kirish & Registratsiya Most bet uz xalqaro bukmekerlik kompaniyasi

“Most bet” bukmekerlik kontorasi 2009 yilda tashkil etilgan bo’lib, dunyoning 93 mamlakati mamlakatida faoliyat yuritmoqda. Interfeys 25 tilga tarjima qilingan, o’nlab sport turlari bo’yicha garovlar qo’yilgan, bu ko’plab xalqaro foydalanuvchilar borligini ko’rsatadi.

Mostbet.uz da ro’yxatdan o’tish 18 yoshdan boshlab barcha foydalanuvchilar uchun mavjud. Bukmekerning ish oynasi yosh o’yinchilar uchun akkaunt yaratishga imkon beradi, lekin ular to’lov tizimlari orqali yutuqlarni chiqarib ololmaydilar. Siz mosbet rasmiy veb-saytiga kecha-kunduz kirishingiz mumkin, kirish kompyuter yoki mobil ilova orqali amalga oshiriladi.

Ikkinchisini soxtalaridan qutilish uchun faqat BKning saytidan mostbet-uz yuklab olish tavsiya etiladi.

Mostbet da ro’yxatdan o’tish bir necha marta bosish bilan amalga oshiriladi va 3 daqiqadan oshmaydi. Agar siz pul tikish va pulni chiqarib olishni istasangiz, sizga pasport bilan tekshiruvdan o’tish kerak bo’ladi. Mostbet uz shaxsiy kabinetga kirgandan so’ng darhol o’yin valyutasini va interfeys tilini tanlashingiz kerak. Boshqa Sozlamalar standart bo’yicha qoldirilishi mumkin.

Mostbet Uz da O’zbekistonda online ro’yxatdan o’tkazish

Mostbet apk -ni veb-saytining mobil va desktop versiyalari o’rtasida deyarli hech qanday farq yo’q. Mobil versiyada moostbet mobil telefon orqali ro’yxatdan o’tish qulayroq, kompyuterda esa elektron pochta orqali. Shuningdek, Mostbet -ga kirish jarayonida ijtimoiy tarmoqlardan ham foydalaniladi. Bu bukmeker mostbetcom SHK-da bo’lishning eng tezkor usuli.

Elektron pochta orqali

- MostBet.com ro’yxatdan o’tish tugmasi yuqori o’ng burchakda joylashgan.

- Keyin «elektron pochta» yorlig’iga o’ting va ma’lumotlaringizni kirgizing.

- Shundan so’ng siz kartadan yoki boshqa usul bilan 15 000 so’m miqdorida hisobingizni to’ldirishingiz kerak bo’ladi.

- Tranzaksiya yangi foydalavchi uchun bonuslarga ega bo’lish va mostbet logo shaxsiy kabinetiga kirish imkonini beradi.

- Barcha sozlamalarni tog’irlab qilib, sayt interfeysini o’rganib chiqqandan so’ng, siz tikishni boshlashingiz mumkin.

sayt mostbet.com Android va iOS uchun Mosbet UZ APK ilovasini yuklab olish

Ljtimoiy tarmoqlarga ulanish orqali

Facebook, VK, Mail, Twitter, Telegram, Steam va Odnoklassniki orqali bir marta bosish orqali MostBet kazino -ga kirishingiz mumkin. Agar ijtimoiy tarmoqdagi akkaunt kompyuterda yoki mobil ilovada allaqachon ochilgan bo’lsa, BK mosbet.uz ga kirish avtomatik ravishda sodir bo’ladi. Kirish uchun ma’lum bir ijtimoiy tarmoqni tanlashdan oldin mostbet.uz o’ynashni rejalashtirgan valyutani qo’yish juda muhimdir.

Telefon raqami orqali

Mostbet rasmiy veb-saytiga kirish smartfon orqali ijtimoiy tarmoqlar, pochta va telefon raqamidan foydalanish orqali amalga oshiriladi. Bu yerda siz ro’yxatdan o’tish formasini bosishingiz va tegishli yorliqni tanlashingiz kerak. Raqam va parolni kiritgandan so’ng, o’yinni mostbet uz com -da boshlashingiz mumkin.

Shaxsni tekshirish yoki verifikatsiya

Mostbet com -da pulni olish bilan rasmiy kirish faqat pasport orqali amalga oshiriladi. Shaxsiy ma’lumotlarsiz pul tikish orqali o’yinchi pulni qaytarib ololmaydi. Mostbetuz.com -da tekshirish LK da qo’llab-quvvatlash xizmati yordamida amalga oshiriladi. Siz «Profil», «shaxsiy ma’lumotlar» ni ochishingiz va ma’lumotlarni kiritishingiz kerak. Agar mostbet uz com -da verifikatsiya bo’lmasa, foydalanuvchi depozitlar kiritishi, pul tikishi, lotereyalar va turnirlarda qatnashishi mumkin, ammo karta, telefon yoki boshqa usul bilan ham yutib olingan summani ololmaydi.

Bukmeker veb-saytida ro’yxatdan o’tgandan keyin yana nima muhim

| 🎁 Bonuslar | 💳 To‘lov usullari | 💱 Qabul qilinadigan valyutalar | 🔑 Promokodlar |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Mostbet uz com casino veb-saytida shaxsiy kabinet yaratilgandan so’ng uning imkoniyatlari va xususiyatlarini o’rganish kerak.

- Ro’yxatdan o’tishda beriladigan bonuslar. Yangi boshlovchilar uchun mostbet uz.com hisob raqamini kamida 15 000 so’m miqdorida to’ldirishda 125% bonus mavjud. Shuningdek, 2, 3 va undan keyingi depozitlar uchun bonuslar mavjud.

- Agar hisob bloklangan bo’lsa, nima qilish kerak. 24 soatlik texnik yordamga murojaat qiling. Mosbet com operatorlari rus yoki davlat tillarida 10-15 daqiqa ichida javob beradi.

- Blokirovkaning mumkin bo’lgan sabablari. Asosiysi, noto’g’ri ma’lumotlarni taqdim etish, hisob yoki depozitlar bilan firibgarlikka shubha qilish bo’lishi mumkin.

- Akkauntga dostupni qanday tiklash mumkin. Mostbet.uz blokirovka sababini aniqlash kerak va uni yo’q qilish kerak. Keyin administratsiya hisobni tekshiradi va shikoyatlar bo’lmasa, unga kirish huquqini qaytaradi.

Mostbet ofisining o’ziga xos xususiyati – bukmeker hech qanday sababsiz muvaffaqiyatli mostbet o’yinchilarining akkauntlarini bloklamaydi. Agar kelishmovchiliklar bo’lsa, siz qo’llab-quvvatlash xizmatiga murojaat qilishingiz va tezkor javob olishingiz mumkin.

Mostbet Uz O’zbekiston bonuslari

Mostbet bukmekerlik kontorasi yangi foydalanuvchilar uchun bonuslar, maxsus takliflar va aktsiyalarning keng doirasiga ega. Doimiy o’yinchilar uchun yutuqlarni ko’paytirishga imkon beradigan sodiqlik dasturi mavjud. Quyida Mostbet bonusini qanday olish va uni saytda faollashtirish tasvirlangan.

Most bet uz.com -da bonuslarni olishning bir necha yo’li mavjud: rasmiy veb-saytda, mobil saytida, ilovada, shuningdek ishlatilgan gadjet va platformadan qat’i nazar, bukmekerning har qanday oynalarida. Ro’yxatdan o’tish paytida mostbet ru bonuslari faqat BK avvalgi veb-saytida akkauntlari bo’lmaganlarga beriladi. Mostbet uz online -ning doimiy mijozlari sodiqlik dasturiga, promo-kodlarga va depozitni to’ldirganlik uchun mukofotlarga e’tibor berishlari kerak. Bonusni olish uchun siz BK ning avvalgi asosiy lobbisida ro’yxatdan o’tishingiz kerak.

MostBet da depozitsiz bonus mavjud, ammo u ro’yxatdan o’tmasdan berilmaydi, shuning uchun mostbet uz apk -da ShK yaratish uchun telefon raqamini yoki elektron pochta manzilini ko’rsatishingiz kerak. Maxsus takliflar ijtimoiy tarmoqlar orqali yoki bir marta bosish orqali ro’yxatdan o’tganlar uchun ham mavjud.

Bukmeker bonuslarining turlari

Bonus takliflari o’yinchilarga pul tikishga bo’lgan qiziqishni yo’qotmaslikka yordam beradi va o’yinchi balansiga bonus mablag’larini qo’shish orqali g’alaba qozonish ehtimolini oshiradi. Mostbet com bukmekerida foydalanuvchi mukofotlarining uchta asosiy turini ko’rib chiqaylik.

- Depozitsiz bonus. Bu shunchaki mostbet uz.com -da ro’yxatdan o’tish uchun olinadi, hisob raqamiga pul kiritishni talab qilmaydi. Bonus moliyalashtirishni nazarda tutmaganligi sababli, faqat birinchi depozitni ko’paytiradi yoki bepul aylanishlarni qo’shadi, uni pulsiz olgandan keyin pul tikish mumkin emas. Siz to’g’ridan-to’g’ri ro’yxatdan o’tish sahifasida o’yinchining ehtiyojlariga mos keladigan mostbet uz bonusini tanlashingiz mumkin. Bu barcha yangi o’yinchilarni qamrab oladi, ammo tajribasiz gembler uchun o’ynash qiyin. Mostbet mobile -dan qo’shilgan foizlarni olish uchun sizga quyidagilar kerak bo’ladi – bonusdan 5 baravar ko’p miqdorda garov tiking. Bunday holda, voqea koeffitsienti kamida 1,4 bo’lishi kerak, o’yin uchun bir hafta beriladi.

- Birinchi depozit bonusi. Mostbet.com uz yangi foydalanuvchilar uchun Xush kelibsiz bonusini birinchi depozitni amalga oshirganlik uchun hisoblaydi. Sovrin foydalanuvchi tomonidan o’yin sifatida tanlangan valyutada beriladi va uning hisobiga pul kiritiladi. Qabul qilish shartlari orasida:

- Faqat yangi o’yinchilar uchun tog’ri keladi;

- Birinchi depozit 15000 so ‘m miqdorida to’ lanadi;

- Ro’yxatdan o’tgandan keyin 7 kun ichida Mostbet BK -da bonus olishingiz mumkin;

- Sovg’aning maksimal summasi-3,5 mln so ‘ m;

- Agar o’yinchi ro’yxatdan o’tgandan keyin 15 daqiqa ichida hisobni to’ldirsa, u 100% bonus emas, balki 125% oladi.

Mosbet ro’yxatdan o’tish shakli

Sovrin hisobning umumiy miqdorini oshirish va kattaroq pul tikish imkonini beradi. Uni o’ynash uchun sizda 1 oy bor. Pul mablag’larini yechib olish uchun siz bonus miqdorining 5 barobari miqdorida pul tikishingiz kerak. Mostbet kazinolari va sport garovlaridagi voqealar koeffitsienti 1,4 dan bo’lishi kerak.

Sovrin sizga hisobning umumiy miqdorini oshirish va katta pul tikish imkonini beradi. Uni o’ynash uchun 1 oy vaqt beriladi. Mablag’larni chiqarish uchun sizga bonus miqdoridan 5 baravar ko’p pul tikilgan bo’lishi kerak. Mostbet kazino va sport garovlaridagi voqealar koeffitsienti 1,4 dan bo’lishi kerak.

- Hisobni to’ldirish uchun bonuslar. Doimiy o’yinchilar uchun alohida mukofotlar tizimi mavjud-ikkinchi, uchinchi, to’rtinchi va keyingi depozitlar uchun bonuslar. Mukofot pullarini qaytarib olish uchun siz sovrin miqdoridan 5 baravar ko’p pul tikishingiz kerak. Tikish uchun 30 kun beriladi. Siz Ekspress ga bet qilishingiz mumkin, shunda koeffitsient muhim bo’lmaydi, agar betlar hodisalarga alohida qilingan bo’lsa, u kamida 1,4 bo’lishi kerak. Mostbetuz.com ni kazinoda mukofotlangan foizlarni tikishda, garovlarning umumiy miqdoridan tashqari hech qanday shartlar mavjud emas.

Qo’shimcha bonuslar

Qo’shimcha mukofotlar sifatida bukmeker ma’muriyati o’nlab aktsiyalar va maxsus takliflarni taklif qiladi. Ular orasida:

* Mostbet uz -da freebet ekspressini sug’urta qilish. Agar foydalanuvchi yetti yoki undan ortiq voqealar bilan ekspressga qo’ygan bo’lsa, unda voqealardan biri yutilgan bo’lsa, balansga qayta o’ynash uchun fribetlar berilishi mumkin.

* «Do’stlarigni taklif qil» aksiyasi mostbet com -da yo’naltirish dasturini faollashtirishni o’z ichiga oladi. Taklif qiluvchi o’z murojaatlari sportga yoki kazinoga qo’yadigan pulning 40 % olishi mumkin.

* Foydalanuvchining tug’ilgan kunida bukmekerlik kontorasi fribetlarni taqdim etadi. Ularning soni mostbet uz casino gemblerining o’yin faoliyatiga bog’liq.

* Mostbet kuponlarini tarqatish. Uch yoki undan ortiq voqealar bilan ekspressga pul tikishda beta-versiyaning 40 % gacha bo’lgan bonusli kuponlarni olish imkoniyati mavjud.

* Har juma kuni depozitni to’ldirgan foydalanuvchi o’z hisobiga kiritilgan summani 100 foizigacha olishi mumkin.

* Xavfsiz stavka. Faqat eng yuqori darajadagi mostbet.uz futbol o’yinlari uchun amal qiladi. Agar foydalanuvchi jamoasi yutqazgan bo’lsa, voqealarga qo’yilgan summaning 100 foizigacha qaytarish mumkin.

Ko’p sonli maxsus takliflarni hisobga olgan holda mostbet.uz geymerlari hisob raqamiga katta miqdordagi mablag’ni olishlari va faqat bonus mukofotini aylantirib o’z pullarini kiritmasliklari ham mumkin. Mostbet promo–kodini olishga muvaffaq bo’lganlar ayniqsa omadli. Barcha mablag’larni qaytarib olish standart rejimda amalga oshiriladi.

Sodiqlik dasturi

Mostbet bonuslari, Promo-kodlari va boshqa mukofotlardan tashqari, BK mostbet doimiy o’yinchilar uchun maxsus qo’llab-quvvatlash tizimini joriy etdi. Sodiqlik dasturi 10 darajadan iborat bo’lib, sport yoki kazinoda mag’lubiyatga uchragan taqdirda mostkoinlar olish imkonini beradi. Mostkoinlar soni bet hajmiga, shuningdek hodisa koeffitsientiga bog’liq. Kelajakda koinlar bonuslarga o’zgartiriladi, 1:5 veydjerida oynalgan song asosiy hisob raqamiga o’tkaziladi. Foydalanuvchi darajasi qanchalik yuqori bo’lsa, koinlarni almashtirishda shuncha ko’p pul bo’ladi.

Mostbet Uz tizimiga kirish

Mostbet uz rasmiy veb-sayti foydalanuvchilar uchun kirish uchun maxsus cheklovlar qo’ymaydi, biroq bir qator qoidalar mavjud. Ular orasida:

- Yosh cheklovlari – faqat 18 yoshdan oshgan o’yinchi mostbet com bukmeykerida ro’yxatdan o’tishi mumkin. BK-ni aldashga urinish shaxsiy hisobni yutuqlarni olib tashlamasdan blokirovka qilishga olib keladi.

- Akkaunlar soni bo’yicha cheklovlar mavjud – har bir foydalanuvchi uchun o’zaro kompensatsiya stavkalarining oldini olish uchun mostbet uz com -da faqat bitta shaxsiy kabietga ruxsat beriladi.

- O’yinchining lobbisiga bog’langan bank kartasi unga tegishli bo’lishi kerak. Tegishli tekshirish mostbet apk 2020 -da ro’yxatdan o’tgandan so’ng darhol tekshirish paytida amalga oshiriladi.

Mostbet online bukmeykerining rasmiy veb-saytida boshqa muhim cheklovlar ko’zda tutilmagan, ammo avval foydalanuvchi shartnomasi bilan tanishib chiqishingiz kerak va faqat keyin o’yinni boshlasangiz bo’ladi.

Mostbet -ga mablag ‘ kiritish va chiqarish

Mostbet uz com -ni to’ldirish faqat ro’yxatdan o’tgan foydalanuvchilar uchun mumkin. Birinchi depozitni qo’yishdan oldin siz pasport ma’lumotlarini tekshirishingiz (tekshirishingiz) kerak, ammo bu protsedura moliya kiritilgandan keyin ham amalga oshirilishi mumkin. Mostbet uz bukmekerlik idorasining shaxsiy hisob balansini to’ldirish uchun quyidagi amallarni bajarish kerak:

- Mostbet App mobil ilovasi yoki dekstop versiyasi orqali portalda ro’yxatdan o’ting. Ro’yxatdan o’tish elektron pochta yoki ijtimoiy tarmoqlar orqali amalga oshiriladi. Profilni uchinchi shaxslarning kirish huquqidan himoya qilish uchun tezkor bosish orqali ro’yxatdan o’tish tavsiya etilmaydi. Pochta va mobil raqamga bog’langan holda darhol mostbet hisobini yaratish yaxshiroqdir.

- BK da avvalgi ro’yxatdan o’tgandan so’ng, siz saytga kirishingiz va sozlamalar menyusi orqali shaxsiy hisobingizga o’tishingiz kerak. Mostbet uz com -dagi Profil ma’lumotlarida Foydalanuvchining holati, asosiy parametrlari va imkoniyatlari, tekshirish zarurati, shuningdek to’lov operatsiyalarining xususiyatlari to’g’risida ma’lumotlar mavjud bo’ladi.

- Mostbet uz com hisobini to’ldirish Foydalanuvchining qabulxonasidagi asosiy menyusi orqali amalga oshiriladi, ammo eng oson yo’li to’g’ridan – to’g’ri saytning asosiy sahifasida «balans» ni bosishdir. Tizim avtomatik ravishda o’yinchini pul o’tkazish shakliga o’tkazadi, u erda siz pul o’tkazish usulini tanlashingiz mumkin.

Android mobil ilovasidan foydalanish uchun kamida Android 4.0 (kamida Android 5.1 tavsiya etiladi) operatsion tizimiga ega qurilmalar kerak boʻladi. Shu bilan birga, oʻrnatish uchun 1 GB operativ xotira va taxminan 200 MB boʻsh joy kerak boʻladi.

O’tkazmaning minimal miqdori, shuningdek komissiyaning foiz stavkasi darajasi tanlangan operatsiya usuliga bog’liq.

Mostbet Uz da hisobni to’ldirish usullari

- Bank kartasidan – MИР, Visa, MasterCard kabi kartalar qabul qilinadi (xorijiy kartalarni VPN orqali qayta ishlash mumkin);

- Elektron hamyonlardan foydalanish – Yandex koshelyok, QIWI, WebMoney;

- Kriptovalyuta hisobidan – mostbet com to’lov uchun kriptoning 20 turini, shu jumladan Bitcoin ham qabul qiladi;

- Mobil tarjima orqali – «Bilayn», «Tele2» operatorlari va bir qator mahalliy operatorlar xizmat ko’rsatadi.

Mostbet -dagi balansni to’ldirishdan oldin, pul o’tkazmasini amalga oshirish rejalashtirilgan karta yoki hamyonda etarli miqdorni tekshirish tavsiya etiladi.

Mostbet apk -dan qanday qilib pul chiqarib olish mumkin

Mostbet.uz pul mablag’larini olishning turli usullarini taklif etadi, bu miloddan avvalgi ishonchlilik va uning ishlashining barqarorligini ko’rsatadi. O’yin hisobi to’ldirilgan bir xil to’lov xizmatlaridan foydalangan holda pulni olish mumkin. Faqatgina cheklov shundaki, o’yinchilar foydalanishi mumkin

Bitcoin faqat balansni to’ldirish uchun xisoblanadi, pul olish uchun emas. Mostbet live -dan qanday qilib pul olish mumkin:

* Saytdagi ShK lobbisiga o’ting va «pulni chiqarish» tugmasini bosing;

* Ko’rsatilgan maydonda pul o’tkazish uchun to’lov tizimini tanlashingiz kerak bo’lgan ro’yxat paydo bo’ladi, qabul qiluvchining rekvizitlarini ko’rsating shuningdek pulni olish uchun miqdorni belgilang;

* Shuni esda tutish kerakki, o’tkazish uchun minimal miqdor to’lov tizimining turiga bog’liq. Masalan, bank kartalari uchun bu 1500 so’mni tashkil etadi. Agar kerakli miqdor balansda bo’lmasa, to’lov amalga oshmaydi;

* Mostbet uz com -da pul mablag’larini olish operatorlar va emitent banklarning ish hajmiga, shuningdek tanlangan pul o’tkazish usuliga qarab bir necha daqiqadan 5 ish kunigacha davom etadi.

Quyidagi jadvalda bukmeker veb-saytidan yutuqlarni qaytarib olish xususiyatlarini korishingiz mumkin.

| To’lov tizimi | Min-Max summa | Vaqt | Komissiya |

| Bank kartasi | 15000-1 500 000 so’m | 5 min-5 kun | 0% |

| Elektron hamyonlar | 1500-1 500 000 so’m | 5-60 daqiqa | 0% |

| Plastrix, FKWallet* | 1500-1 500 000 so’m | 15 min-3 kun | 0% |

| Mobil balansi | 1500-150 000 so’m | 10-30 daqiqa | 0% |

Pul mablag’larini olishda keng tarqalgan xatolar – bu mostbet android -dagi o’yin hisobiga kiritilgandan so’ng darhol pulni chiqarib olishga urinish, boshqa birovning bank kartasidan foydalanish, boshqa hisobga o’tkazish.

Mostbet mobil ilovalari

Telefon ilovasini rasmiy Google Play va App Store do’konlaridan yuklab olishingiz mumkin. Siz Mostbet apk 2021, Mostbet apk 2020, Mostbet apk 2022 -ni Android va boshqa smartfonlar uchun mostbet uz aviator veb-saytidan yoki «mostbet apk download» qidiruv tizimidagi so’rov bo’yicha yuklashingiz mumkin.

Android uchun Mostbet yuklab olish

Saytda mostbet.uz apk ilovasini yuklab olish uchun rasmiy havola mavjud. O’rnatish o’rnatuvchini ishga tushirgandan so’ng boshlanadi. Mostbet portali osilmaydi, u hamma uchun oson ishlaydi platforma versiyasi va tez-tez yangilanishni talab qilmaydi. Mostbet apk 2022 -ni yuklab olish uchun havolani bosing.

Mostbet iPhone uchun yuklab olish

Mostbet download -ga havola barcha avloddagi iPhone-lar uchun ham ishlaydi. Most bet aviator ( aviator mostbet ) -da onlayn o’yin dasturlarini yuklab olish va sport yoki kazino tikish mutlaqo xavfsiz.

| Apk faylning oxirgi versiyasi | Mostbet_5.9.3.apk |

| Oʻrnatish fayli hajmi | 22,68 MB |

| Oʻrnatishdan keyin mobil qurilmada joy egallaydi | Taxminan 150 MB |

| Tillar | 35 ta til, jumladan, oʻzbek tili |

| Yangilanish chastotasi | Har 1-2 oyda bir marta |

| Toʻlov tizimlari | Uzcard, VISA, MasterCard, Ripple, Paybet, Uzpayments, LimonPay, kriptovalyutalar va boshqalar (29 ta toʻlov tizimi) |

| Bonuslar | Mostbet welcome bonuslari, CashBack, Kupon soyuvi, G’alabalar jumasi, Ekspress-buster, Tug’ilgan kun Mostbet bilan, Kazino sodiqlik, Xavfsiz stavka dasturi va boshqalar. |

| Roʻyxatdan oʻtish usullari | 1 bosishda, telefon orqali, E-mail orqali, ijtimoiy tarmoqlar orqali |

| Sportga pul tikish | Ha (Prematch, Live) |

| Onlayn kazino | Ha (jumladan, Live casino) |

Mostbet -da sportga tikish

Miloddan avvalgi betalarni turli tadbirlar uchun qabul qiladi va sodiqlik dasturini yaratadi. Dastur darajalari, holatlari va sovg’alarini mosbet ShK-da ko’rish mumkin. Dasturda ishtirok etishni boshlash uchun sizga promo-kod yoki boshqa fokuslar kerak emas. Mostbet uz com -da ro’yxatdan o’tish, depozit qo’yish va odatdagidek pul tikish kifoya. Har bir o’yinchi dasturda avtomatik ravishda ishtirok etadi.

Barcha yangi foydalanuvchilar Sport tikish paytida Mostbet fribetni olish imkoniyatiga ega. U darhol mostbet shaxsiy hisob qaydnomasida olinadi yoki foydalanuvchining elektron pochtasida mavjud bo’lishi mumkin.

Mostbet coins yo’qolgan betlar uchun beriladi. Bunday holda, beta hajmi va hodisa koeffitsienti muhim emas-koinlar har qanday holatda ham hisoblab chiqiladi. Mostbet uz -dagi asosiy balans tugmachasini bosgandan so’ng, o’yinchi hisobida allaqachon ko’rsatilgan garovlardan bonuslar sonini bilib olishingiz mumkin.

Live stavkalari

Jonli voqealar yoki jonli voqealar sizga katta koeffitsientni olish imkonini beradi, shuningdek, BK-da keshbek funktsiyasi mavjud. Mostbet uz -da keshbek uchun o’yinchi chegara miqdorini yo’qotishi kerak. Qaytish haftada bir marta dushanba kuni amalga oshiriladi, agar betalar asosiy hisobdan bonus mablag’laridan foydalanmasdan amalga oshirilgan bo’lsa, haftaning barcha stavkalari asosida hisoblanadi.

Kibersport

Mostbet apk android virtual futbol, xokkey, poker va boshqa o’yinlarga pul tikish imkoniyatiga ega. Har bir bet uchun o’yinchining tajribasi va darajasi oshadi. Mostbet kazinosida «nol» dan tashqari 9 ta o’yinchi darajasi mavjud. Har bir levelga erishish uchun mostkoinlar beriladi, ular pulga o’tkaziladi va o’yinchining hozirgi darajasiga bog’liq bo’lgan pul tikish orqali o’ynaladi.

Siz depozit qo’yishda, shuningdek kazinodan kunlik vazifalarni bajarishda qo’shimcha ball to’plashingiz mumkin. Kvestlar har 24 soatda yangilanadi, bu esa har kuni koinlarni olish imkoniyatini beradi. Olingan koinlarning pul uchun ayirboshlash kursi, shuningdek, garov va o’ynash vaqti o’yinchining darajasiga bog’liq.

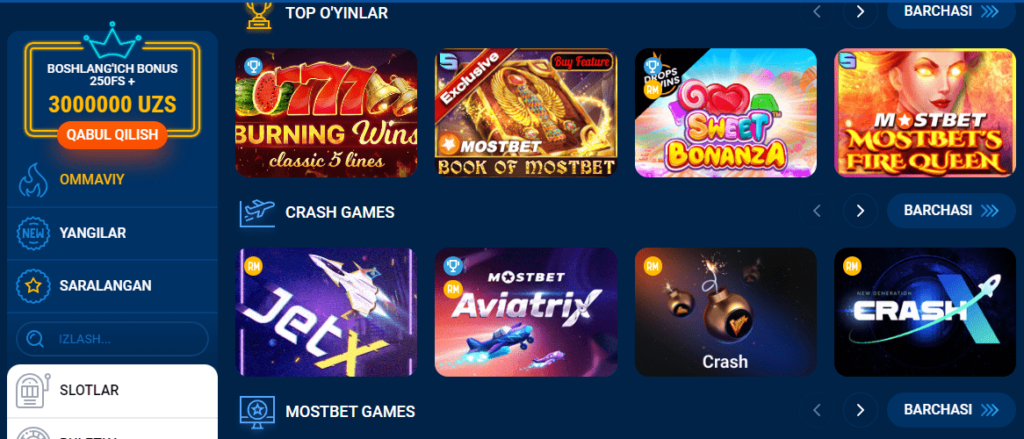

Mostbet onlayn kazinosi

Slotlarda va mashinalarda o’ynashni afzal ko’rgan foydalanuvchilar uchun alohida sodiqlik dasturi mavjud. Bu ko’p jihatdan sport tikish uchun taqdim etilganiga o’xshash, ammo sezilarli farqlar ham mavjud. Bu erda siz Ruletka, poker, BlackJack va yuzlab uyalarni o’ynashingiz mumkin. Mostbet mobile -dagi har bir taklif uchun ballar beriladi. Foydalanuvchi ro’yxatdan o’tgandan keyin va o’yin davomida ba’zi vazifalarni bajarayotganda birinchi juftlarni oladi. Sodiqlik dasturlari yashash joyidan qat’i nazar, barcha foydalanuvchilar uchun mo’ljallangan. Ularni faollashtirish uchun ma’lumotlarni tekshirish shart emas, ammo saytdan pul olishda yosh va pasport ma’lumotlarini tekshirish talab qilinadi.

Mostbet Casino-dagi mashhur slotlar

Ljtimoiy tarmoqlar orqali

VK va boshqa ijtimoiy tarmoqlar orqali MostBet -ga garovlar mostbet mobile veb-saytiga yoki mostbet apk -ga havolani bosganingizda amalga oshiriladi. Bukmeker ma’muriyati doimiy o’yinchilar uchun shaxsiy hisob balansidagi pul sonini ko’paytirishga va o’ynashni davom ettirishga yordam beradigan qo’shimcha aktsiyalar va maxsus takliflarni yaratdi. Ijtimoiy tarmoqlarda siz yaqin atrofdagi voqealar haqida bilib olishingiz va pul tikishni boshlashingiz mumkin.

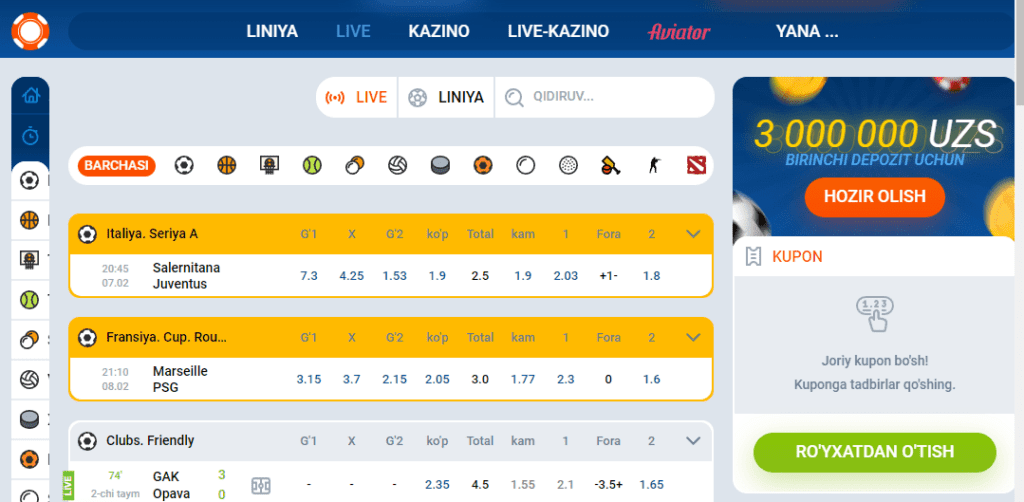

Mostbet liniyasi va koeffitsientlari

Mostbet apps -da siz bir vaqtning o’zida bir yoki bir nechta qatorga qo’yishingiz, Ekspress yoki jonli tadbirlarni tanlashingiz mumkin. O’yin davomida koeffitsient darajasi o’zgarishi mumkin, ammo g’alaba garov tikilgan koeffitsient bo’yicha hisoblanadi. Agar o’yinchi garovining o’ynashiga amin bo’lmasa, ular sotib olish opsiyasidan foydalanishlari mumkin.

Maxsus taklif har qanday darajadagi o’yinchilar uchun mavjud. Agar voqea koeffitsienti o’yinchi foydasiga keskin o’zgarmasa, zudlik bilan pul kerak bo’lsa, jamoalar tarkibi o’zgargan yoki boshqacha bo’lsa, garovni sotib olish kerak. Garovni sotib olish uchun shaxsiy hisobingizdagi «garovlar tarixi» ga o’tishingiz kerak. Aksiya faqat ordinar yoki ekspressda qilingan sport tikishlari uchun amal qiladi.

Jonli rejimda (Live) yoki o’yin oldidan etkazib berilgan mablag’larni sotib olishga ruxsat beriladi. Maxsus shart – voqea garovni sotib olish belgisi bilan belgilanishi kerak. Joriy koeffitsientga qarab, bet miqdori, shuningdek boshqa holatlar sayt avtomatik ravishda qaytarish miqdorini hisoblab chiqadi va uni Foydalanuvchining shaxsiy kabinetiga o’tkazadi. Qaytish miqdori, albatta, etkazib berilganidan kamroq bo’ladi, ammo bu sizga barcha pullarni emas, balki ularning faqat bir qismini yo’qotishga imkon beradi.

Mostbet qo’llab-quvvatlash xizmati

Agar foydalanuvchi mostbet.com veb-sayti bilan shug’ullana olmasa, u texnik yordamga murojaat qilishi kerak.

* Texnik qo’llab-quvvatlash kecha-kunduz ishlaydi, foydalanuvchi bilan aloqa u lobbida tanlagan tilda amalga oshiriladi.

* Siz mutaxassislarga onlayn chat, elektron pochta yoki telefon orqali murojaat qilishingiz mumkin.

* Murojaat qilishda muammoning mohiyatini aniqlashtirish, skrinshotlarni taqdim etish, aloqa ma’lumotlarini ko’rsatish muhimdir.

* Texnik yordam yuklanishiga qarab 5 dan 15 minut ichida javob beradi.

- Ko’pgina hollarda, muammo foydalanuvchi operatorlarga murojaat qilganidan keyin dastlabki 30-60 daqiqada hal qilinadi.

Gambling o’yinchilari va mutaxassislarining fikriga ko’ra, Mostbet boshqa BK-larga nisbatan eng samarali texnik yordam dasturini amalga oshiradi.

Foydalanuvchilarning fikrlari

BK -ning mashhurlikning doimiy o’sishini hisobga olgan holda, foydalanuvchilar uning funktsional imkoniyatlari, koeffitsientlari va yutuqlarining kattaligi bilan ajralib turadi. Forumlarda va tematik guruhlarda sharhlarni tahlil qilgandan so’ng, bukmekerning asosiy ijobiy tomonlari aniqlandi:

* Har bir tikish uchun Cashback. Hisob raqamga pulni qaytarish faqat yo’qotilgan garovlar uchun mavjud, cashback miqdori hisob-kitob davri uchun yo’qotilgan miqdorga bog’liq.

Foizlarni hisoblash haftada bir marta yakshanbadan dushanbaga o’tar kechasi amalga oshiriladi. Bir hafta ichida kamida 15000 so’mdan kam bo’lmagan pul tikganlar va o’tgan haftaga nisbatan minusda bo’lmaganlar qaytarib olishlari mumkin. Foydalanuvchilarga pulni qaytarib olish uchun 72 soat vaqt beriladi, shartlar kazino va sport tadbirlariga pul tikish larga tegishli.

* Ekspress-kuchaytirgich yutuq hajmini 10% ga oshirishga imkon beradi. Asosiy shart-to’rt yoki undan ortiq voqealar bilan ekspressga pul tikish. Hodisalarning har birida minimal koeffitsient 1,2 bo’lishi kerak. Variant avtomatik ravishda faollashadi, o’yinchidan qo’shimcha harakatlarni talab qilmaydi. Agar Ekspress g’alaba qozonsa, foydalanuvchi o’z yutuqlarini va uning 10 foizini bukmekerlik idorasidan sovrin sifatida oladi.

* Promo kodlarining mavjudligi. Mostbet bonuslaridan biri – ro’yxatdan o’tish paytida promo-kod-tasdiqlanganidan keyin Foydalanuvchining elektron pochtasiga kelishi mumkin. Siz kodlarni bukmeykerlarning sherik saytlarida, pochta xabarlarida, ijtimoiy tarmoqlarda va messenjerlarda BK rasmiy kanallarida topishingiz mumkin.

* Vaqtinchalik bonuslar. Vaqtinchalik bukmeykerning ma’lum bir amal qilish muddati bilan cheklangan barcha aktsiyalari va maxsus takliflarini o’z ichiga oladi. Vaqtinchalik aktsiyalar o’yinchilarning faolligini oshirish va ularning bettingga bo’lgan qiziqishini oshirish uchun yaratiladi. Odatda takliflar yuqori darajadagi futbol o’yinlari yoki boshqa sport tadbirlari paytida faollashadi.

Shuningdek, o’yinchilar BK to’lovlarni kechiktirmasligini va barcha pullarni qonuniy ravishda olish va o’ynash qoidalariga rioya qilish sharti bilan Foydalanuvchining hisob raqamiga o’tkazishini ta’kidlaydi.

Мостбет– bu sizning yutuqlaringiz uchun eng yaxshi o’yinlar, sport tadbirlari va kazino imkoniyatlari bilan tanishish uchun yaxshi joydir. Bizning platformamizda siz o’yinlarni yoki sport tadbirlarini tanlashingiz mumkin va qulaylik bilan pul ishlash imkoniyatiga ega bo’lasiz. Bizning kazino ham sizga eng yaxshi o’yinlar va yutuqlar bilan xizmat qiladi. Sizga qulaylik va rahatlik taqdim etish uchun, МОСТБЕТ sizning yutuqlaringiz uchun eng yaxshi o’yinlar, sport tadbirlari va kazino imkoniyatlari bilan tanishish uchun eng yaxshi joydir.

Kazino va qimor

Qimor o’yinlari hayotimizning bir qismi bo’lgan va ularning o’ziga xos o’zgarishlari bilan bizni qiziqtiradi. МОСТБЕТ kazino orqali sizning qimor tajribangizni yanada oshirishingiz mumkin. Bizning kazino platformamizda sizga eng sevimli o’yinlardan birini topishga imkon beriladi.

Kazino o’yinlarimizning keng qamrovli ro’yxati sizni hayratga soladi. Siz o’zingizga qulay bo’lgan o’yinlarni tanlashingiz mumkin: ruletka, blakjak, poker, bakara va boshqalar. Har bir o’yin o’ziga xos qoidalarga ega bo’lib, sizga qiziqarli va qimmatbaho sovg’alar taklif etadi.

МОСТБЕТ kazino platformasi sizga yuqori sifatli grafika va animatsiyalar bilan dizayn qilingan o’yinlarni taklif etadi. Siz o’zingizga qulay bo’lgan interfeysni tanlashingiz mumkin va o’yinlarni mobil qurilmalarda ham o’ynashingiz mumkin.

Qimor o’yinlarida qiziqishni yo’qotmang! МОСТБЕТ kazino orqali sizning qimor tajribangizni yanada oshiring va yutuqlar qozonganingizni his qiling!

Mostbet bukmeyerida roʻyxatdan oʻtish

Mostbet bukmekerlik idorasi haqida ko’p so’raladigan savollar

Mostbet uz-ni qanday yuklash mumkin?

Rasmiy veb-saytidan yoki Google Play va Appstore do’konlaridan.

Mostbetda sportga qanday pul tikish mumkin?

Garovlar qabulxonaning asosiy sahifalarida amalga oshiriladi. Hisobni to’ldirish, chiziqlardan voqeani tanlash va bet miqdorini ko’rsatish kifoya.

Mostbet bukmeykeriga pul tikish kerakmi?

BK ning eng xavfsizlardan biri bo’lib, halol to’lovlar va foydali koeffitsientlar bilan ajralib turadi.

Balansni qanday to’ldirish kerak?

«Moliya» bo’limidagi «to’ldirish» tugmachasini bosing, o’tkazmaning qulay usulini tanlang va bitim miqdorini ko’rsating.

Mostbet Uzcard yordamida hisobni qanday to’ldirish mumkin?

Yuqoridagi banddan amallarni bajaring, karta raqamini va uning egasining ismini ko’rsating. Ism hisob egasining ismiga mos kelishi kerak, tekshirish uchun ma’lumotlarni tekshirish ishlatiladi.

Bukmekerga ilova orqali kirish mumkinmi?

Ha, mobil ilovalar ishlaydi va doimiy ravishda yangilanadi.

Android va iOS-da promo kodlaridan foydalanish mumkinmi?

Ha, promo kodi ro’yxatdan o’tish paytida yoki Ekspress liniyasiga pul tikishdan oldin kiritiladi.

MacOS uchun dastur bormi?

Hozirda dastur mavjud emas, ammo BK brauzer versiyasiga kirish imkoniyati mavjud.

MostBett -dan yutuqlarni qanday chiqarib olish mumkin?

«Moliya» yorlig’iga o’ting, pulni olish (chiqarish) variantini bosing, operatsiyaning qulay usulini tanlang va o’tkazma miqdorini ko’rsating.

Ushbu blog muallifi sifatida men Mostbet platformasini shaxsan sinab ko’rdim va ishonch bilan aytishim mumkinki, u e’tiborga loyiqdir. Sayt o’z foydalanuvchilari uchun sport tadbirlarining keng tanlovini, qulay interfeysni va ko’plab foydali bonuslarni taklif etadi. Men barqaror va tezkor to’lovlarni ham ta’kidlamoqchiman – bu shaxsiy tajriba orqali tasdiqlangan muhim jihat. Agar siz ishonchli va ishlatish uchun qulay bukilish platformasini izlayotgan bo’lsangiz, Mostbet ajoyib tanlovdir!

Men bir qancha vaqtdan beri Mostbet veb-saytidan tikish uchun foydalanaman va taassurotlarim faqat ijobiy emas. Platforma juda qulay, siz birinchi marta pul tikayotgan bo’lsangiz ham, hamma narsa intuitivdir. Sport tadbirlarining keng tanlovi zavqlantiradi va bonuslar va aktsiyalar jarayonni yanada qiziqarli qiladi. Bundan tashqari, to’lovlar o’z vaqtida keladi, bu men uchun muhim nuqta edi. Umuman olganda, Mostbet ishonchli va qulay tikish platformasini qidirayotganlar uchun ajoyib saytdir!

Men Mostbet-dan bir qancha vaqtdan beri foydalanaman va sayt mening umidlarimni oqlaydi. Mostbet UZ-da hamma narsa sodda va qulay – sport tadbirlarining katta tanlovi, aniq interfeys. Bonuslar va aktsiyalar, albatta, pul tikishda yordam beradi. Pul olish tez va kechiktirmasdan amalga oshiriladi. Agar sizga O‘zbekistonda ishonchli tikish sayti kerak bo‘lsa, Mostbet UZ ajoyib imkoniyatdir.